In this post, I give a brief introduction to Roslyn analyzers, what they're for, and how to create a simple analyzer in Visual Studio 2017. I'll show how to create a code analyzer that targets .NET Standard using the new Visual Studio 2017 (15.5) templates, and show how you can debug and test your analyzer using Visual Studio. As the code in Roslyn analyzers can be a bit complex, I'll look at the actual code for the analyzer in a subsequent post - this post just focuses on getting up and running.

.NET and Visual Studio enable you to develop data-centric, modern line of business applications (LoB) for Windows. Create visually stunning user experiences with WPF or use WinForms productive WYSIWYG designers to incorporate UI, media, and complex business models. If you close all instances of Visual Studio and delete those two folder you’ve reset the experimental version of Visual Studio with the id Exp. If you’re using another parameter after /rootsuffix like Roslyn then the two folders would be somehting like: Roslyn and 15.018f5488bRoslyn.

This is my post for the C# Advent Calendar. Be sure to check it out in the run up to Christmas for a new post every day!

Visual Studio Roslyn Cache

Why create a Roslyn Analyzer?

I was recently investigating some strange bugs which would only sporadically manifest in an ASP.NET app recently. Long story short, eventually the issue was traced back to a Task not being awaited. This was causing concurrency issues that were hard to spot in the code, as everything compiled correctly. For example

By default, you will get compiler warnings if you don't use await inside an async method. The problem was, we were using await for some of the calls in the offending method, just not all of them. By awaiting a single Task, the compiler was satisfied, and no warning was issued for the second method.

As an aside, this is one of the main arguments for preferring the Async suffix for async methods. Even with a rich IDE like Visual Studio, the issue in the above code was not picked up - when reviewing code statically (e.g. on this blog or in GitHub), the Async suffix is the only indication that there's anything awry in the second call.

Once we identified the problem, the question was how to prevent it happening again. Naming conventions and code-reviews can go some way towards mitigating the issue, but it seemed like there should be a more robust technical solution for detecting un-awaited tasks. That solution was a Roslyn Analyzer.

In this post I'll introduce analyzers in general, and show how to get started. In a later post, I'll show the solution we came up with for the above problem.

What are Roslyn analyzers

Analyzers are effectively extensions to the C# Roslyn compiler, which let you add extra warnings and errors to your code, in addition to the standard compiler errors. You can use these to enforce naming styles and code conventions, or to flag particular code patterns, such as the missing await in the above code.

Analyzers can be distributed either as a NuGet package, or as a VSIX extension for Visual Studio. If you install the analyzer as a VSIX extension, it'll automatically be used in all of your projects, but other people building your projects won't use the analyzer. On the other hand if you reference the analyzer as a NuGet package in a project, everyone who builds your project will see the same compiler warnings and errors, you just have to remember to install it

In Visual Studio, analyzers installed as extensions or as NuGet packages hook into the UI. You'll see green/yellow/red squigglies depending on the severity associated with your analyzer, and you can even associate your analyzer with a Code Fix to perform automatic refactorings:

If you're using an editor other than Visual Studio, you won't get these UI enhancements, but by referencing the NuGet package you'll still get the compiler warnings and errors when you build your project.

If you're writing cross-platform code (or even if you're not) I strongly suggest installing the API Analyzer. This will highlight framework API calls that are deprecated, or which might throw PlatformNotSupportedExceptions on certain platforms.

Creating a Roslyn analyzer

Up until recently, creating a Roslyn Analyzer that could be consumed anywhere was a bit of a chore. You had to install various extensions from the Visual Studio marketplace, and even then the project templates produced PCL projects, which requires a different build chain to normal .NET Standard projects. When I created my first analyzer, half the battle was converting the project to be compatible with .NET Standard.

I was therefore very happy when writing up this post to see that the Analyzer projects in Visual Studio 2017 are now .NET Standard by default! I think that happened in update 15.5, but I'm not 100%. Either way, it makes the experience much smoother, so I'm going to assume you're already on Visual Studio 2017 15.5 for this post.

1. Install the Visual Studio Extension Development Workload

The first step is to install the necessary components for building Analyzers and VISX extensions in Visual Studio. You don't have to install the VSIX components, but even if you're always going to distribute your analyzer as a NuGet package, it makes the debugging experience much smoother, as you'll see later.

Open the Visual Studio Installer program from your start menu, and click the Modify button next to your installed version of Visual Studio:

From the Workloads page, scroll to the bottom and select the Visual Studio extension development workload. This installs the .NET Compiler Platform SDK, the Visual Studio SDK, and other prerequisites. Depending on which other workloads you have installed it should use an additional 150-300MB of drive space.

Once that's installed, open Visual Studio, and we'll create our first analyzer.

2. Create an Analyzer with Code Fix

There are a variety of new templates made available by installing the Visual Studio workload, but the one we're interested in here is the Analyzer with Code Fix (.NET Standard). You can find it under Visual C# > Extensibility:

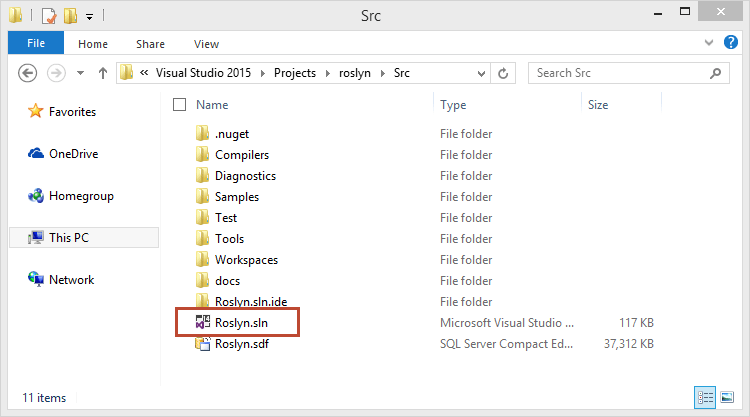

Give your project a name (the imaginative Analyzer1 in my case), and let Visual Studio do it's thing. Once the template is created (much faster than usual in update 15.5 I have to admit) you'll have a solution with three projects:

- Analyzer1 - This is the Roslyn analyzer and Code Fix project. It contains the code that you will package into a NuGet and deploy.

- Analyzer1.Test - Tests for the analyzer. We'll look at these in more detail shortly - but effectively you pass some C# code stored in a string to the analyzer under test, and check you get the expected results.

- Analyzer1.Vsix - A Visual Studio VSIX extension project that can be used to deploy your analyzer. More importantly (for me) it can also be used to Debug your analyzer in action inside an instance of Visual Studio.

The default project template creates a basic, but complete, Analyzer and CodeFix which requires that all class names should be entirely uppercase (I said it's complete, not useful). The Code Fix lets you click the light bulb (or ctrl+.) when the analyzer detects a class with lowercase letters, and replace the type with its uppercase equivalent.

At this point, rather than digging into the analyzer code itself, I'm going to show Visual Studio's party trick - debugging an analyzer while it's running in another instance of Visual Studio!

Debugging your analyzer inside Visual Studio

If you're new to working with the Roslyn compiler directly, then the code in an analyzer can be daunting. Lots of types with somewhat obscure names can make it difficult to get a foothold. For me, one of the best ways to get to grip with it was the ability to Debug my code as it was running in another instance of Visual Studio. That sounds like it would be a pain to set up, but it actually works out-of-the box, just press F5!

Make sure that the VSIX project is your solution's current startup project (it's shown in bold in Solution Explorer and it's listed in the Startup Projects box next to the Debug button):

When you hit Start or press F5 to debug, your project is compiled, and a Visual Studio extension is created. Visual Studio then starts up a new copy of Visual Studio and installs the extension into it.

I haven't looked into the specifics, but when you debug a VSIX project in this way, I believe it uses a different profile to your normal Visual Studio profile. When you first Debug, you'll see the Visual Studio startup screen asking to setup your environment:

Note the small black debugging bar at the top of the window - this is an easy way to tell whether you're looking at your main Visual Studio window or the debugging window! As this is a separate Visual Studio profile, your recent projects list will be empty:

If you check in Tools > Extensions and Updates you may also find that some of your extensions are missing. However, importantly you'll see that our analyzer, Analyzer1, has been installed:

Don't worry, all of these changes are only in the Debug session of Visual Studio - your existing Visual Studio instance and settings won't be affected. Any changes you make to the Debug instance are persisted across sessions though.

If you create a new Console project, you'll see that the analyzer immediately picks up the lowercase letters in the Program class name, and gives it a green squiggley - this is the analyzer at work. In the quick fix light bulb menu, you'll see an option for Make uppercase - this is the Code Fix in action.

This is all very nice, and lets you test your analyzer in action, but you can also properly debug the analyzer code. If you set a breakpoint in your analyzer project, you can step through the code as it's executed in the other instance of Visual Studio. Pretty cool :)

This approach is great for experimenting and exploring issues, but you can also unit test your analyzers, as shown in the Analyzer1.Test project.

Testing your Analyzer and CodeFix

Roslyn is effectively a 'compiler as a service'. You can pass it a string containing C# code, and it will compile it, allowing you to ask semantic questions about the contents, including running your analyzer.

Creating a unit test for the sample project is simple, thanks to some helper classes added to the project by default, in particular the CodeFixVerifier base class. Simply create a string containing the C# code to test, define the expected analyzer results, and call VerifyCSharpDiagnostic() as shown below.

This compiles the provided string, and runs your analyzer against the compilation result. As you can see, this test verifies that our analyzer flags the class TypeName as containing lowercase letters, and defines the position in the string (which is given the placeholder name 'Test0.cs') that the warning should be placed.

You can run similar tests for the Code Fix, in addition to the analyzer. Simply pass the expected string after the Code Fix has been applied to the VerifyCSharpFix() method. After the Code Fix has executed, the TypeName class has been renamed to TYPENAME:

Summary

In this post I showed how to install the necessary components to build Roslyn analyzers, why you might want to, and how you can Debug and test your analyzers, using the default project templates. In the next post, I'l take a look at the code in the default analyzer template, and look at building the await analyzer described at the beginning of this post.

This is a step by step guide on how to create a C# Roslyn Analyzer project for Visual Studio.

Requirements¶

Note

This guide was tested using:

- Version 1.4 of the .NET Standard framework for the .NET Standard project that has the analyzers.

- Version 4.6.2 of the .NET Framework for the unit test project.

- Version 2.2.0 of the nuget Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.CSharp.Workspaces.

- Visual Studio 2017 Version 15.2

See here for more information on what nuget versions you should use.

The quick and easy way¶

Once you have installed the .NET Compiler Platform SDK you can get started quickly by using the built in templates to create a new analyzer project.Go to File->New->Project then select Extensibility under Templates->Visual C#.

Make sure the .NET framework version selected is 4.6.2 and you will be able to seea template called Analyzer with Code Fix (Nuget + VSIX).

Once you have created your new project the template will create three projects for you:

- A portable class library: where the code for your analyzer is. This project is also configured to produce a nuget package upon building.

- A test project: this test project is quite handy since it serves as a starting to point to how you can test your analyzers.

- A VSIX project: this has two purposes. It produces a VSIX file which can be used to install your analyzers as a Visual Studio Extension and it will also enable you to debug your analyzer.

And you’re set to go. I advise you to explore the default analyzer (DiagnosticAnalyzer.cs) and code fix provider (CodeFixProvider.cs) that are created as part of the template in the portable class library project as well as the tests (UnitTests.cs) that are in the test project.

The #Pro way¶

Although templates are great to get you started they might not fit your case. Also if you want to understand how everything works then this section will give you a better understanding of all the magic that the default template does for you.

Creating the project for your analyzer code¶

Let’s start by creating a blank solution. Once the blank solution is created we need to add a new project to it that will serve as the project where the code for your analyzers is. Although the template creates a portable class library project you are free to select another type of project as long as there is support from the .NET Compiler platform SDK for it.

Visual Studio Roslyn Error

In this case let’s create a .NET Standard Class library project. Go to File->Add->New Project, select .NET Standard under Templates->Visual C# and then select Class Library (.NET Standard).

Now let’s edit the project so that we can install the nugets we require to create our analyzers. Right click the project and select Edit.

Edit the cs proj file in order to set the PackageTargetFallback as follows:

Save and close the cs proj file and add the following nuget to the .NET Standard project:

- Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.CSharp.Workspaces version 2.2.0.

Creating the debug project¶

The debug project as the name suggests will allow you to debug the code of your analyzers. For that we will create a VSIX project. VSIX projects are used to create extensions for Visual Studio and although we are creating a VSIX project the intent is not to then distribute the resulting VSIX file. We could do that and when users installed the VSIX file they would have access to the analyzers you’ve developed but for distributing the analyzers I think a nuget package is better.

The VSIX project is still what we want because once configured and set as the startup project it will launch an experimental version of Visual Studiothat is being debugged by the Visual Studio process that launched it (the one that has your analyzer solution). This will allow you to create a new project and test your analyzers with break points to aid your development.

Go to File->New->Project then select Extensibility under Templates->Visual C#. Make sure the .NET framework version selected is 4.6.2 and you will be able to see a template called VSIX Project.

Once you’ve created the VSIX project you get three files:

- stylesheet.css: you can delete this since you don’t need it.

- index.html: you can delete this since you don’t need it.

- source.extension.vsixmanifest: this one is where you configure the properties for your extension.

We need to configure the source.extension.vsixmanifest so that it uses the analyzer project we created in the previous step.Double click the source.extension.vsixmanifest and:

- Change the Product Name on the top to be what you want.

- Give it a description.

- On the Assets tab click new and add an entry with a Type of Microsoft.VisualStudio.MefComponent. On Source select A project in current solution and in the Project select the project that has the code for your analyzers. In our case it would be the .NET Standard project created in the previous step. Leave the Embed in this folder empty and click OK.

- On the Assets tab click new and add an entry with a Type of Microsoft.VisualStudio.Analyzer. On Source select A project in current solution and in the Project select the project that has the code for your analyzers. In our case it would be the .NET Standard project created in the previous step. Leave the Embed in this folder empty and click OK.

By adding an asset of type Microsoft.VisualStudio.Analyzer you have enabled the code for any analyzer you create in the analyzers project to be packaged by the VSIX project. And by adding an asset of type Microsoft.VisualStudio.MefComponent you have enabled the code for any code fix provicer you create in the analyzers project to be packaged by the VSIX project.

As a last step make sure the VSIX project will launch an experimental version of visual studio. This should be set by default but confirm by going to the VSIX project properties and checking that the Debug tab has the following:

- Under Start action the option to Start external program should be selected and the location should be where you have installed visual studio. Something like C:/Program Files (x86)/Microsoft Visual Studio/2017/Enterprise/Common7/IDE/devenv.exe.

- Under Start options the Command line arguments should be set to /rootsuffix Exp

Creating the test project¶

Just create a regular unit test project and add the following nugets:

- Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.CSharp.Workspaces version 2.2.0.

Now you can reference the .NET Standard project and create your tests. I recommend that you copy the folders Helpers and Verifiers that are created as part of the test project when using the template Analyzer with Code Fix (Nuget + VSIX). See The quick and easy way. These classes contain methods that will greatly help you understand how to test your analyzers and code fixes.

In my own projects I’ve copied and changed the classes in these folder so that I could use them the way I wanted but they will work fine if you use them as they are.